Home | News | Books | Speeches | Places | Resources | Education | Timelines | Index | Search

Michael W. Kauffman

© Abraham Lincoln OnlineMICHAEL W. KAUFFMAN, ASSASSINATION DETECTIVE

Part II: Walking in Booth's Shoes

This is the remainder of our interview with Michael W. Kauffman, author of American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, conducted in September 2007. Kauffman describes how he tried to understand his subject, Abraham Lincoln's assassin, as he was pursued by federal authorities through Maryland and into eastern Virginia. Booth eluded capture for 12 days before being shot in a burning tobacco barn.We call Kauffman a "detective" because his methods remind us of Sherlock Holmes, the famous fictional sleuth. When you read his comments below, you'll notice similarities, too: a strong ability to observe, analyze, search, and combine the results in an imaginative way. At the end of the page, you'll see a question-and-answer section.

If you missed Part I: Looking Through Booth's Eyes, click here to see how Kauffman researched and compiled his book.

Editor's Note: Since this interview, Kauffman published In the Footsteps of an Assassin in 2012, which details the route Booth took through Maryland and Virginia.

Rowing Across the Potomac River

Kauffman: I didn't set out to work with a you-are-there approach. Instead, I wanted to do the Booth escape route in various ways so I could understand what Booth would have seen and done and felt like. A Washington Post reporter invited me to go along when he tried to reproduce Booth's rowing trip across the river. As we set out I had lots of questions about the river and what happened when he crossed it. I had a mental picture of the conspirator George Atzerodt who rowed the river for years and figured he must have looked like Popeye with big, muscular arms. So I'm looking for that, the currents, the weather, and why Booth didn't make it across that first night from Maryland to Virginia.One of the big puzzles is that Thomas Jones said he had gone for years rowing across the river and went undetected, yet so many ships were out there. It made no sense. How could someone go without being seen on a flat surface such as water? I still don't know how, but I believe it. When we were rowing, we got about a quarter mile from the photographer's boat and lost track of him. We looked around, wondering where he went. He had fallen back a little ways to take some pictures from a distance. That's all. I still have not figured out how it's possible for a boat to virtually disappear, yet it happened.

Once on the river it became obvious that on the open water, as calm it was that day, there's still quite a breeze. It would have been impossible to keep a candle lit as Booth needed to. What would he have done if he couldn't see the compass? If you hold the candle at the bottom of the boat to protect it from wind you get a sore back, and soon give up. You also need to be quiet if a ship approaches. To remain undetected, all you can do is stop rowing and maybe pull in the oars and lie down. I hadn't thought of that before going out there.

Many people have tried to explain why Booth headed one way and ended up somewhere else. Would Thomas Jones, who put Booth onto the river, want Booth to set out when the tide's coming in or out? As it turns out, it doesn't make any difference. That's because the Potomac does some strange things at that point. It flows to the northeast, then makes a sharp bend to the south. Another river feeds into it right at the turn. The current is unbelievably strong there, and it goes in circles. Crossing from one side to another, you'll encounter some resistance in both directions. And by the way, the river is very deep and dangerous there. They say if you fall in you may not be found for a couple of weeks. So it doesn't matter where you try to cross. You just go when you need to.

That convinced me that I shouldn't rely so much on theory. You can't just consult tide charts. You have to put yourself in there and ask people who have experience rowing in the area. I'm a big believer in personal experience, and being out there on the water helped seal it for me. Although I learned a lot, that trip was actually a little disappointing. The Washington Post reporter did not allow enough time to get all the way across, so when the sun went down he had us towed the rest of the way. I was looking forward to coming back as Booth described himself -- "wet, cold, and starving, with every man's hand against me." We talked about trying it again, but somehow we never did.

It may not be possible to do it again. A Navy base is nearby and after September 11, 2001, they shoot first and ask questions later. I did, though, get a call from a man who works on the base. He said, "I've got a canoe. Do you want to come out and do Gambo Creek?" What an opportunity! I can't say no to that. So we canoed up the creek, looking for where Booth and his companion, David Herold, might have put their boat on the shore. And guess what? There's only one place all along there where you can actually walk away from the creek. In most places the banks are too steep, or the swamp is too soupy. The old bridge was right there, and since the tide was so low, we could see wooden pylons in the water.

That makes perfect sense. A bridge marks the location of a road, and since Herold had to walk around in search of Mrs. Quesenberry's house, what better way to do it than to follow a road? It was very exciting so see what most people don't get to otherwise. Again, things fall into place when you go check it out for yourself.

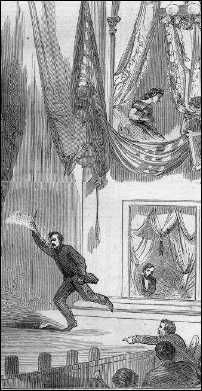

I knew this wasn't the real thing, but I couldn't stop anything. I've played the scene over and over in my mind, and mentally, I could always back things up for a closer look. But this was very different. Here's a man who walks in, shoots someone, drops the gun, pulls out a knife, slashes at another man, and leaps to the stage. All the while I'm watching this and I'm powerless to stop it. My heart skipped a beat. It was like going down a hill, but when you put your foot on the brake nothing happens. It was a very mild version of what the original audience must have experienced when they started to figure out what had just happened. Though this took place after my book came out, it was still a valuable lesson. I'll never forget it.

Booth at Ford's Theatre

Harper's Weekly

Jumping onto Ford's Theatre Stage

There was a story going around in 1995 that Booth hadn't actually died in 1865. That was a very old story, revived by Unsolved Mysteries, and it led to a lawsuit in which I testified as an expert witness. The publicity was unbelievable, and since so many people came away with the impression that we were merely covering up for the government, I wanted to do a documentary on the facts of the case. I went to some extremes, traveling all over the country, even burning down a tobacco barn. We had an actor in Ford's Theatre and 50 or so re-enactors as the audience, plus Jim Getty as Abraham Lincoln.Of course the National Park Service wouldn't let anybody jump out the presidential box, so we had to fake it for the cameras. I thought we'd have a 12-foot ladder there next to the box, and crop the shot so it looked like Booth was coming down, and we'd cut to another shot of him landing. Just to demonstrate, I started climbing the ladder and got a wild idea, but dared not ask permission. So I got to the top and just did it. I didn't jump out of the actual box. Someone snapped a picture, and since I was wearing a green shirt, I looked like a giant zucchini plummeting to the stage.

A year and a half ago I was invited to attend a re-enactment in the theatre for someone's film project. They couldn't use the original box, but went to great expense and trouble re-creating everything in the opposite box. They pointed the camera into a mirror and let me look through the viewfinder and I got chills.

Everything was in reverse: the music, Honor to Our Soldiers, was printed backwards, the audience playbills were backwards, Lincoln's and Henry Rathbone's hair was parted on the wrong side; they thought of everything. On that occasion the actor actually fired a derringer and leaped to the stage. He had no hesitation. He said later, "It's no big deal." That was an experience. That was like being there, and it's as close as I'd want to get.

I heard from a church that had a barn on their property. They wanted to build a new church and were going to tear it down anyway. It was perfect because it appeared to be well over 100 years old. We decided to start filming in the wee hours of the morning. Our "Boston Corbett" had some counter-insurgent experience in the Army but he couldn't get a fire going. Finally they went off and got something to help it along. A delay like that must have happened in Booth's time. They probably did a lot of talking back and forth. Certainly Booth had time to think about what he was going to do. The suspense was too much for Herold, and he was already tired of running anyway. There were soldiers all around the barn, and they surely knew they had a long wait ahead of them, too.

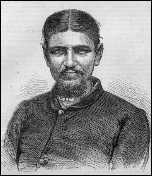

Boston Corbett

Harper's Weekly

Firing an Old Tobacco Barn

Burning down a tobacco barn also taught me important lessons. How long it takes, for example, for an old, dry barn to catch fire -- which is quite a while. In this case we were trying to make a documentary. We got some cavalry re-enactors who knew all about the life of a cavalry soldier, including a man who resembled Boston Corbett playing Corbett. They had all the right weapons and insignia for the Sixteenth New York Cavalry as well as the horses. I had advertised for a tobacco barn somewhere in southern Maryland because they don't have that type of barn in Virginia anymore.That was an important point. If you catch somebody off guard, what they do is by impulse, a reflex action. That wasn't the case with Booth. He had time to think. If he thought of shooting his way out, it was a deliberate action rather than a quick motion misunderstood by others. The soldiers who surrounded him got a bit of a bad rap, especially Boston Corbett, who killed Booth.

Most people still believe that there were orders not to shoot, to take Booth alive. That story was started by Luther Baker, who made the claim for one reason: to discredit Corbett, who got so much attention. So Baker and his cousin, Lafayette Baker, made up stories, and for most people those tales seemed perfectly logical. But the truth was on paper, under oath, from Luther Baker himself and from Everton Conger, the other detective at the scene. Conger specifically said that no one had given orders to shoot or not to shoot. Naturally they would want to bring Booth to justice on their own terms, but it didn't work out that way, and nobody expressed regret until later.

Think of how cruel it would be to tell a pursuer, "Go out and find this killer and bring him back alive. If you bring him back dead you get nothing; alive, you get $50,000." Under those terms, anyone would hesitate to defend himself. If Booth raises a weapon and points it at him he's at a serious disadvantage. He's got two choices: dodge a bullet and take cover, or dodge a bullet and rush Booth to capture him alive. Either way it's deadly. That's why the policy has always been "dead or alive."

Related Questions

Did anyone consider Booth as a hero? A few people have asked if I thought Booth was a hero. One of the book reviews even claimed as much. That really bothers me. Although Booth was an interesting person, mostly because he was unexplained for so long, I can't see him as anything other than a cold-blooded manipulator. No matter how you feel about Abraham Lincoln, you have to see Booth as a guy who cared about nobody. The word he used was "sacrifice." People who turned down his pleas to join the plot -- good, decent people -- are the ones who probably suffered the most because they were very nervous about going to prison or losing their lives after what Booth said to them. He seemed to have no conscience about that. David Herbert Donald had it right when he said that I've presented Booth as an even bigger monster than we ever knew. That's certainly the way I feel.I also want to make it clear that the book is called American Brutus, but the title was meant to be ironic. Booth may have wanted to be Brutus, but Lincoln was certainly no Caesar. In Booth's world, Brutus was a hero, and he might have been a hero in the founding period as well. But America was no longer that insecure. The country had grown and thrived, and they no longer feared the loss of free government, as earlier generations had. And they were no longer looking to the past for political guidance -- at least, not the way they once did. Booth didn't get that. All he got was that a lot of people hated Lincoln. With his Shakespearean background and his classical education, the word 'tyrant' jumped out at him, and he figured there was only one way to deal with such people. It didn't matter that the criticism of Lincoln was overdrawn, or that those controversial war measures were a temporary last resort. And though Booth wouldn't have known it, Lincoln was absolutely sincere in his belief that the nation would someday return to normal with all its freedoms intact.

What I hope comes through in all this is that by studying Booth you have to study the opposition. That's where you'll discover how violent and threatening the opposition was. More important, they were close at hand -- in New York City and other places, often within sight of the White House.

Lincoln certainly knew that. He always knew that his course of action would probably get him killed. But he never backed down. Only when you see that do you really appreciate the tremendous courage he showed. But the Union was important to him, and in saving it, he reshaped and strengthened it so that nobody could ever again express doubt about the effectiveness of free government. In later years there were a lot of people who claimed they had supported Lincoln in this, but some of those claims ring a little hollow.

Late in 1862, when the elections had gone against him and the army had suffered a terrible defeat at Fredericksburg, Lincoln felt almost alone. But he stayed the course. That really showed what he was made of. Regardless of your political views, you can't help but have a whole new respect for the man. Even the most rabid Southerner should have admired Lincoln for his courage if nothing else. Though I come from a long line of Pennsylvanians, I've always had an affection for the South because I lived there for so long. In fact, I attended first grade right around the corner from Jefferson Davis's house in Mississippi, and even at that age, my classmates were talking about the Civil War.

How did Southerners respond to your book? There's a catch-22 here: on one hand people in the North assumed that if I've written about Booth I must like him. On the other, people in the South seem a whole lot less interested because, to them, it's sort of a Lincoln book. Not too many Southern groups have invited me to talk about my book. This is surprising, and kind of disappointing. I should think they would want to embrace it. After all, I wrote that Booth was not acting in their behalf. Lincoln offered a gentle peace for Southerners, and their leaders would have been stupid to order his assassination. And as I also pointed out, Booth's views had much more in common with Northern Democrats than with those of the Confederates.

Do you feel sorry for the conspirators who were executed? Not really. I think Booth misled people, but they were grown-ups, and they made their own choices. In a way I feel badly for George Atzerodt because he wasn't smart enough to see what could happen to him. On the other hand, Arnold and O'Laughlen did know better, and they fled when they realized what was going on. Atzerodt just kind of hung around. He seemed to have no idea that his failure to kill anyone was not a legal defense. He still conspired, even up to the last hour, and I can just imagine how he felt when he realized that his bargaining chip -- the testimony he offered against Booth and the others -- was worthless, since most of what Booth had told him was a lie. As he went through the trial he wore away to nothing, and I couldn't help feeling some pity for him. But again, he made his own choices. He got himself into something that was just wrong. They all did. And they all went to their graves cursing the name of John Wilkes Booth.

Click here for Part I: Looking Through Booth's Eyes

If you haven't already done it, you might pick up a copy of American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies from a library or book source of your choice. This volume describes the story of Abraham Lincoln's murder, the motives of his killer, and the conspirators connected to the plot. You'll be swept into the story because it reads like fast-paced fiction, but it has more than popular appeal. The information rests on an immense foundation of original sources and exhaustive research. Kauffman thinks like a detective as he approaches this pivotal historical event and the characters who populate it.

Kauffman also published a related book in 2012, In the Footsteps of an Assassin, which describes the route Booth took through Maryland and Virginia.

RELATED INFORMATION

Assassination Links

Assassination Books

Home | News | Education | Timelines | Places | Resources | Books | Speeches | Index | Search Copyright © 2007 - 2020 Abraham Lincoln Online. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy